What the UK population will look like by 2061 under hard, soft or no Brexit scenarios

Nik Lomax, University of Leeds; Paul Norman, University of Leeds; Philip Rees, University of Leeds, and Pia Wohland, The University of Queensland

With the British parliament still deadlocked, the UK’s future Brexit strategy is not yet set in stone. Whatever path the UK chooses from here will have an impact on the future of British immigration policy – and therefore on the size of the population.

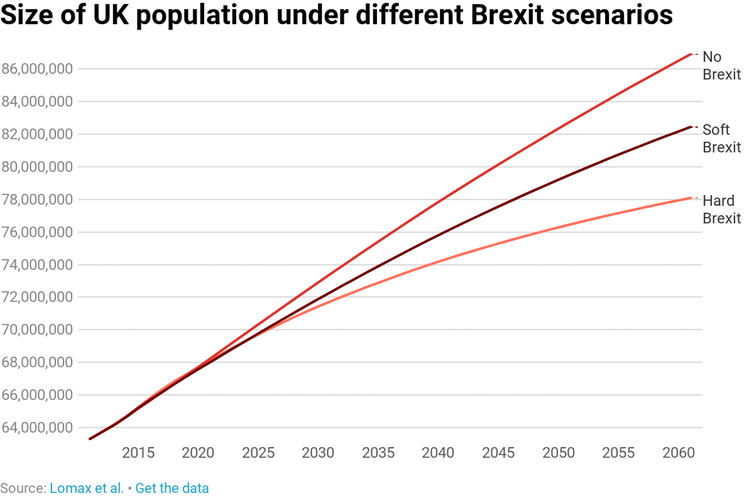

In a new study, we produced a range of population projections for the UK to the year 2061, based on assumptions about what would happen to international migration under three Brexit scenarios: no Brexit, a soft Brexit and a hard Brexit.

We found that under all of the scenarios, the UK population is projected to become more ethnically diverse and older – and that it will continue to grow, albeit at different rates.

Population growth is a key driver of demand for housing, infrastructure, school places, health care and consumption, and so population projections are essential for the effective planning of these services. Of the components which make up these projections, international migration is the least predictable, yet has a large impact on the size and composition of the population. Our scenarios therefore used different assumptions about future immigration policy.

For the no Brexit scenario we extrapolated trends seen in UK total immigration and emigration flows between 1991 and 2014. According to our model, this scenario would see population growth for the next few decades, with a population in 2061 of 86.9m.

For soft Brexit, we took the long-term assumption for net international migration in the national population projections of the Office for National Statistics, based on the population at the end of June 2014. Our model assumed that the free movement of EU citizens would continue, but that a combination of factors would make the UK less attractive to migrants. Under this scenario, the UK population would continue to grow, but at a slower rate than the no Brexit scenario, and by 2061 the total population is projected to be 82.9m.

Under the hard Brexit scenario, we translated the 2010 Conservative Party pledge to reduce net international migration to “fewer than tens of thousands” into assumptions about immigration and emigration flows. Under this scenario, population growth would be slower, reaching 78.1m in 2061.

Taken together, this means that the UK population would be 8.8m people smaller by 2061 under a hard Brexit, compared to if the UK did not leave the EU.

Population ageing under all scenarios

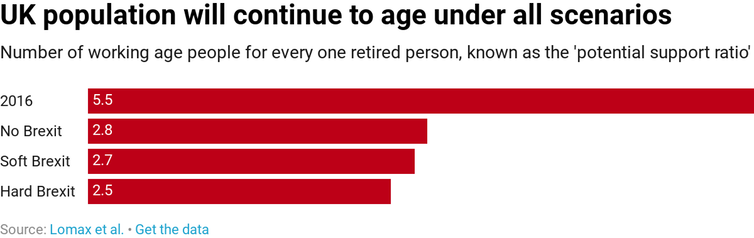

The different scenarios also have an impact on how old the population is. One way of assessing this change is to look at the number of people of working age for every one person who is retired. This measure is called the “potential support ratio” and reveals the challenge for pension, healthcare and social care systems from population ageing. It is a relatively crude measure, but does serve to highlight how the age composition of populations changes over time.

In our analysis, we took people over the age of 70 as a proxy for retirement – taking into account planned and potential changes to the state retirement age – and all people aged between 19 to 69 for the working population, to take into account potential educational commitments of younger people.

The 2016 figure was around 5.5 working age people for every one person over retirement age. Under the no Brexit scenario, this would drop to 2.8 in 2061. It would drop to 2.7 under a soft Brexit scenario while a hard Brexit would result in 2.5 people of working age per retired person. Under all scenarios, there are fewer working age people to support those in retirement.

More ethnically diverse

Our results also showed that the different scenarios would have an impact on the ethnic composition of the population. Understanding the ethnic composition of the population is important for ensuring equality of opportunity and in reducing discrimination. The breakdown is also required for effective planning, because different ethnic groups have varying needs for health care and social care, particularly through the provision of informal care and education through language provision. These differences in need for different services were highlighted by a 2017 comprehensive audit of all UK government data, which revealed that disparities aren’t uniform across all domains for all ethnicities.

As a crude measure, we were able to assess the proportion of the population who aren’t white British or Irish. Under all three of our scenarios, this proportion rises. The 2016 figure was around 17.5%. Under a no Brexit scenario, this rises to 41.9% in 2061. A soft Brexit would see the figure rise to 40.4%, and a hard Brexit to 35.6%. Part of the reason for this rise, no matter what assumptions are made about international migration, is due to demographic momentum, as ethnic minority populations who are relatively young continue to grow as they form families and have children.

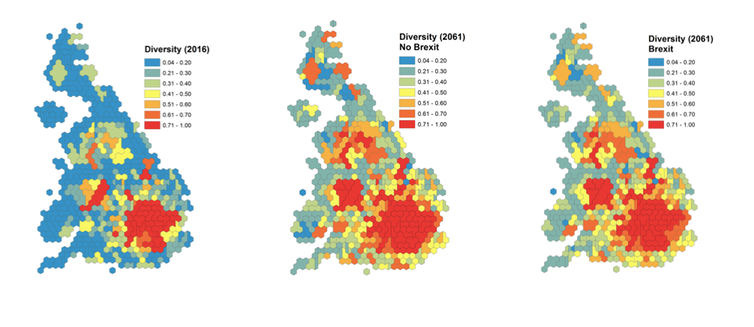

We’ve also projected an increase in ethnic diversity across a large number of local authority districts. This can be assessed by what’s called an “index of diversity”, under which a score of zero represents no diversity – all people belong to a single ethnic group – while a score of one represents complete diversity, where all groups are equally represented.

The maps below show that in 2016, urban areas had the highest ethnic diversity scores (shown in red), while the lowest diversity scores (shown in blue) were in rural and coastal local authorities. Under the Brexit scenario – the map shows the soft Brexit scenario but the results for hard Brexit are very similar – diversity in 2061 would be higher across the UK, with particularly high increases for those local authorities bordering the larger cities.

The hexagon map was designed by Bethan Thomas and Danny Dorling and implemented for the ETHPOP project by Pia Wohland.

Our research shows that under all three different potential Brexit scenarios where international migration assumptions were tested, the UK population is projected to increase in size, become more ethnically diverse and the population structure shifts to one which is older.

These headline changes are seen across the UK, where the majority of local authority districts become more diverse in 2061 than they are now. There are major uncertainties associated with these UK projections, but the scenarios we’ve set out provide a plausible range of outcomes. Those planning future immigration policy would be wise to consider what this means for public services and for society.

Nik Lomax, Associate professor in Data Analytics for Population Research, University of Leeds; Paul Norman, Lecturer in Human Geography, University of Leeds; Philip Rees, Emeritus Professor, University of Leeds, and Pia Wohland, Research Academic, Queensland Centre for Population Research, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.