The recent Channel 5 program “Inside Waitrose” again highlighted the existence of a ‘Waitrose effect’ on the UK housing market.

But what exactly is the effect, and does it apply to homeowners and renters alike? We asked CDRC Researcher, Dr Stephen Clark, to explain.

What is the ‘Waitrose effect’?

The program reported work by retail analyst James O’Malley which identified the location of ‘posh’, high personal income neighborhoods and found that the top 10 poshest neighborhoods contained a Waitrose.

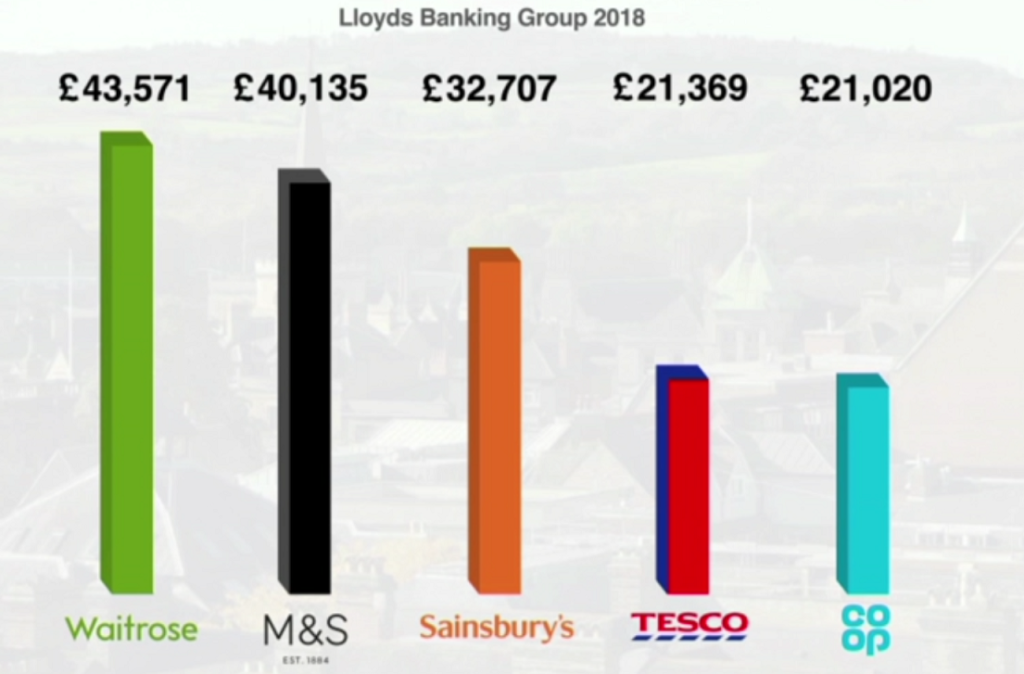

The most often cited study for this ‘Waitrose effect’ was conducted by Lloyds bank in 2018 that quantified the impact of various retail brands on local house prices. This study compared the average house prices in the catchment of various supermarket brands with equivalent prices from farther afield and associated the difference to the presence of the supermarket brand. They found an impact for most major brands, but the highest was for Waitrose, a +9.3% premium.

(source : https://www.channel5.com/show/inside-waitrose/)

Does having a Waitrose or M&S nearby really make such a difference?

Well, what the study did not do is try to control for the other aspects that might drive this difference, for example Waitrose stores may be located close to larger, more expensive properties than in the wider area. This means that the Waitrose effect reported may also be picking up other differences between the local neighborhood and the wider areas.

Whilst this Waitrose effect on house sales is well reported, there is less understanding of the impact of retail brands on other aspects of the English housing market, such as rental properties. This gap in knowledge is what our recent study aimed to fill.

Also, we decided to control for other aspects that make properties more desirable, such as the size of the property, the affluence and character of the neighborhood, access to services and the quality of local schools. This allows us to distill out many of these ‘confounders’ to hone in on a true retailer association.

Another aspect of our study is that we extended the understanding by examining different effects from smaller ‘convenience’ locations and more traditional larger store locations. This is important because the attractiveness of each type of location is different – the range of goods is more limited in convenience stores, but they are allowed to open for longer hours on Sundays.

What data did you use?

For our study we used two main sources for our data. One was a database of over 1 million private rental listing prices taken from the popular Zoopla property listing site, provided by the Consumer Data Research Centre, from July 2014 to December 2015.

The second was the location of retail brands provided by the property analytics company GEOLYTIX, which allowed us to identify the location of stores, their brands and their size. Using powerful analysis software we were able to associate with each property listed for rent in England, the brand of the closest convenience store and the brand of the closest medium to large store.

Other ‘confounding’ information on the size of the property (bedrooms, bathrooms and reception rooms), the affluence of the neighbourhood (through a classification of areas and local incomes), the distance from the property ‘hot spot’ of West London, the quality of local schools and the access to transport hubs was also attached to the property. This comprehensive and diverse database on over 1 million properties allowed us to use regression analysis to measure the association of each of these aspects on the listing price of the property.

So does the ‘Waitrose effect’ have a similar impact on the rental market?

Our model produced reassuring insights. The confounding variables all estimated the correct magnitude and influence on rental prices, e.g. higher rents for larger properties, in more affluent areas that are closer to good schools and railway stations. And the retail findings were also insightful.

Convenience store

Properties that had a convenience store within a handy 500m walking distance showed a positive impact on rental prices, after controlling for all the above confounders, over having no convenience store close by.

The biggest effect associated with a brand was for the little Waitrose brand with a 5.6% increase in rental prices. The impact for Marks and Spencer Simply Food stores was almost as high, with a 5.1% increase. The smallest increase was for a small Co-operative store of just +0.8%. Of the Big-4 retailers, the local brand for Tesco express was favored over Sainsbury’s Local stores.

Medium to large store

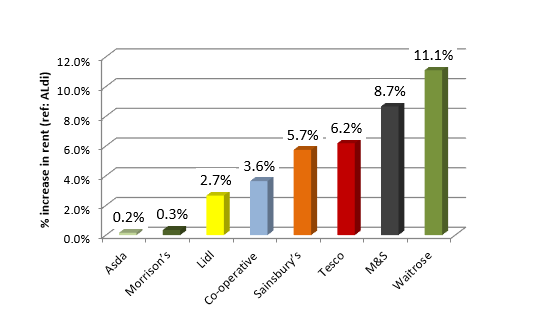

Looking at the influence of which brand of medium to large store was closest to the property (irrespective of distance) and measuring this relative to the Aldi brand, we again see distinct differences by brands. The premium is always positive, meaning that all brands command a premium (all be it small in some case) over the Aldi brand.

Again the Waitrose effect is most pronounced with an associated 11.1% increase in private rental prices. With the house sales data, Lloyds bank estimates a 9.3% increase. The second highest brand is again Marks and Spencer, with an 8.7% increase. Two of the Big-4 retailers, Asda and Morrison’s only showed a small premium over having an Aldi store as the closest retailer.

One interesting finding is that Lidl, Aldi’s fellow discounter, shows a price premium over an Aldi and these two Big-4 retailers. It will be interesting to work out why this might be the case.

Is the ‘Waitrose effect’ London centric?

Waitrose traditionally has its roots in Southern England, particularly around London and London is recognised as an expensive location for property, both to buy and rent. This then leads us to ask are we just picking up an affluence effect from South East England for our brands?

Well, the reason we introduced the confounders was to try and capture any affluence effect in the South East using other information, such as the local income levels, the affluence of the neighbourhood, its socio-demographic make-up and critically, a distance from West London to capture in this one term the reduction in private rental prices as one moves away from West London. What is left in the variation in rents after these confounders have been accounted for is then tested against the retail brands.

What about the future?

Our study gives us a good understanding of the interaction between retail provision and rental prices in the recent past, but this relationship is clearly dynamic. Questions arise around whether in the post-Covid-19 living, working, leisure and retail landscape, will city centres and associated rental housing be less attractive and likely to remain so? Conversely, are more localised residential areas with associated small high streets now more desirable, with a knock on positive impact on convenience grocery stores and nearby rental costs? Has consumers’ experience with on-line retailing weakened the geographic link between where people live and shop – or have local in-store loyalties transferred to into the e-retailing sphere? Clearly this is an active and important area of research that is best facilitated by access to the types of novel data used here.

Do you have any plans for further work in this area?

In this study, for statistical reasons, we can only really claim an association between the retail brands in a neighbourhood and the rent for local private rental properties. To claim an actual causation requires more sophisticated statistical techniques. One technique that we are actively investigating is Propensity Score Matching which attempts to mimic a traditionally randomised control trial type experiment. Here we are attempting to set up a group of control areas (that do not have the retail brand present) and a group of treatment area (that have the retail brand present). If these two groups can be made to look ‘similar’ in every respect other than the presence of a retail brand, then any difference in the rental price may be attributed to the presence of the retail brand. Initial investigations are proving positive.

Further Information

For further information or a copy of our article, please contact Stephen Clark.

The full article is available here: Clark, S., Hood, N., & Birkin, M. (2021). A hedonic model of the association between grocery brand provision and residential rental prices in England. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis.