Earlier this month Dr Francesca Pontin, CDRC Research Data Scientist at the University of Leeds, gave evidence to the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee on ‘Fairness in the food supply’.

Fran provided insight from CDRC-Leeds’ Priority Places for Food Index and the teams wider research. We asked her to share a little bit more about the index and some of the key insights from the committee:

About the Priority Places for Food Index

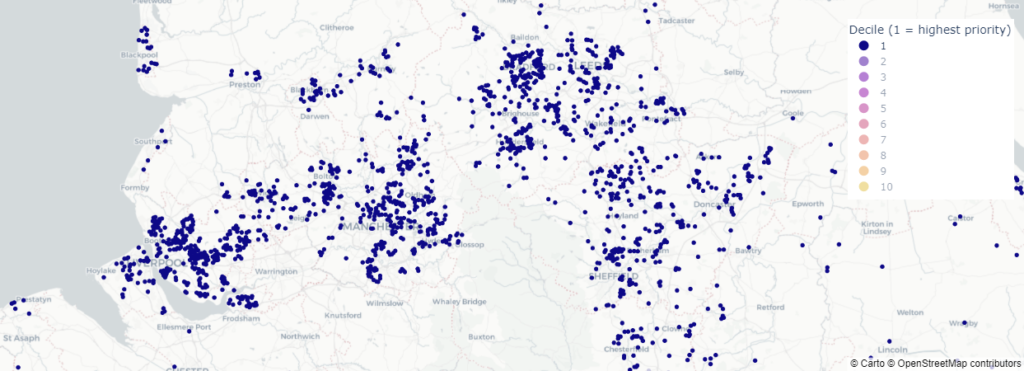

The Priority Places for Food Index (PPFI), developed last year in collaboration with Which?, identifies areas within the UK at risk of food insecurity.

Policymakers can use the interactive map to identify neighbourhoods most in need of support and to understand the main reasons that they need this support.

Transport is part of the problem, and the solution

Household access to a car can be a serious limitation for consumers when it comes to accessing affordable food – not only do they have difficulties reaching food retailers in general, but they are also unable to conveniently shop around for deals, choose cheaper food retailers or ‘bulk buy’ in a way that could minimise cost.

PPFI includes data on household car access and access and availability to public transport. The length of a journey via public transport is part of how we generate our ‘Accessibility to supermarket retail facilities’ data domain. Household access to a car is measured in the ‘Socio-economic barriers’ data domain.

Issues around transportation also look different whether you are in an urban or rural area. Increasing connectivity opens up consumer choice by making a variety of food retailers more accessible to larger portions of society.

Different solutions are needed for urban and rural areas

In rural locations, access to supermarkets often drives the risk of food insecurity. In these cases, meeting both transport need and availability (e.g. increasing local connectivity) would lower the risk of food insecurity.

Longer term, increasing the number of available supermarkets in rural areas would potentially minimise the distance needed to travel to reach those sources of food.

There is also an issue with rural food retailers potentially operating at a higher price point, especially where rural communities might rely significantly on convenience stores for the majority of their shopping. Mystery shopper research from Which? found supermarket-brand convenience stores do not stock budget-range groceries, though Morrisons has now committed to doing so in their Morrisons Daily convenience stores.

In urban areas, the primary drivers of food insecurity risk are typically socio-economic barriers. Shoppers may be able to access supermarkets more easily, but other markers of deprivation captured in the index, including income deprivation, fuel poverty and reliance on food ‘safety-nets’, limit their ability to purchase food.

Pushing health problems down the line

Not having access to adequate amounts of food or the right sources of food is not just a cost-of-living problem, it has far-reaching implications for the future burden placed on our health service.

Fran also highlighted that childhood attainment is one of the outcomes most likely to be impacted by food insecurity, as a lack of adequate nourishment for children makes it harder for them to concentrate in school.

A need for legislation

In October 2022 the Government introduced legislation which limits the sale of foods high in fat, salt, and sugar (HFSS) in key retail promotion locations within retail stores, over a certain size, selling food.

In this session the panel discussed how it is possible for legislation to drive change for businesses. Fran highlighted HFSS as an example of how sector-wide change can happen when it becomes a business priority, putting less burden on health and sustainability teams to make a business case for healthier and more sustainable product lines.

There is a clear need to respond to consumer concerns around food health, sustainability and pricing – and this is part of what PPFI and our ongoing work with Which? allows us to do – however Government legislation can provide an effective top-down approach to ensure businesses act.

The team are involved with the DIO-Food project, an academic evaluation of the impact of the HFSS legislation: whether it worked to reduce sales of HFSS items and whether it impacted communities equally. It will consider both the experience of consumers and retailers. This will allow us to continue making valuable suggestions to Government about what really works in retail settings.

Healthy start top-up vouchers and price incentives

The committee had a number of questions around price incentives on healthy products.

In response to these questions Fran highlighted research from the University of Leeds, in collaboration with IGD and Sainsbury’s in which analysis on a 2021 Healthy Start top-up scheme revealed that baskets redeeming a £2 top-up coupon purchased 13 more portions of fruit and vegetables compared to baskets where a voucher was not redeemed.

Fran also referenced a trial, undertaken in collaboration with IGD and Sainsbury’s which reduced the price of selected fruit and vegetables in stores across the country for four weeks and led to the number of promoted fruit and vegetables sold increasing by 78% during the intervention period.

Food sector data transparency

Academic research can only happen when data are made available for rigorous analysis.

Unfortunately, competition law and commercial sensitivity often limits what data retailers can share externally, including with researchers. Whilst the CDRC has worked hard to establish relationships with retailers to enable data sharing, there are still many challenges when it comes to sharing within the sector.

Whilst much of our work is with large retailers, we also know that smaller retailers such as independents and convenience stores can offer alternative insights. However, working with these retailers presents its own challenges, as they often do not have the internal resource to enable research development and relationships or to share data.

Ensuring food sector data transparency, for example through the Food Data Transparency Partnership would not only allow greater access to food data for analysis, but also create a non-competitive space where retailers could share learnings of what works to help customers. Legislation of this kind would level the playing field, and we would welcome convenience store retailers as part of that conversation.

Large overlap between food sustainability and cost-of-living initiatives

A recent trip to Good Food Oxfordshire, who are using the PPFI as a core metric in the Oxfordshire Food Strategy, highlighted how sustainability initiatives originally set up to minimise food waste have now had to pivot to also solving food insecurity during the cost-of-living crisis.

This has become a particular issue when large redistribution initiatives mean that surplus food is not being kept local but in fact being moved across the UK. Particularly relevant at the moment in light of the King’s The Coronation Food Project announcement, a project which aims to redistribute food surplus to the neediest areas.

It is becoming clear that sustainability initiatives alone are not sufficient to address food poverty, and that there needs to be greater attention paid to the barriers to accessing food, rather than the availability of food, either in retailers or in surplus.

Watch the ‘Fairness in the food supply chain’ evidence session.