November 2020 brought a series of sustainability goals to the forefront with COP26, and linked initiatives such as the Earthshot Prize, rightly monopolising media attention. Tackling climate change was not only of great importance to policy makers in Glasgow, but also to companies and consumers around the world.

Our global food system is the second biggest contributor to climate change [1]. Retailers and manufacturers in the UK food industry are responding to this and are working hard to be a driving force of change. IGD’s Healthy and Sustainable Diets Project Group and WWF’s recent Retailers’ Commitment for Nature are examples of the brilliant collaboration happening in the sector to reduce the toll that our weekly food shops have on the environment.

This November also saw the release of the Institute of Grocery Distribution’s (IGD) Behavioural Insights Report. The report shares the first findings from our ongoing research, in partnership with IGD and their Healthy and Sustainable Diets Project Group, where we look at how healthy choices and sustainable choices can be one and the same.

Can food retailers and manufacturers make the shift towards a healthy and sustainable diet easy, accessible and appealing to consumers at the point they are purchasing and planning their food for the week?

To investigate this, interventions have been co-designed by IGD, members of IGD’s Healthy and Sustainable Diets Project Group and the University of Leeds, to trial one or several of the behavioural levers below.

A 4-week national price reduction trial to encourage greater fruit and veg, tested year on year

The first exciting trial we have been studying is Sainsbury’s ‘60p Fruit and Veg’ campaign.

Looking to increase the amount and variety of fruit and vegetable products in shoppers’ baskets, Sainsbury’s ran a promotional intervention for four weeks in both January 2020 and January 2021. These promotions reduced the price of selected fruit and vegetables to 60p in store and online.

Signposting and placement were used alongside incentivisation to draw attention to the offer. Our research aimed to determine whether this multi-levered approach led people to make healthier and more sustainable choices, and monitor whether any change was sustained in the nine months following the trial.

The trial was varied each year in the selection of fruit and vegetables chosen for the offer: thirteen products were on offer in 2020 and seven in 2021. Furthermore, the first trial in 2020 was outside of national lockdowns, whereas the second trial, in 2021, occurred during one.

Studying 23.4 million baskets

For our initial findings, we analysed national unit sales data for 23.4 million baskets that contained a promoted fruit or vegetable item between January 2019 and March 2021. Following the sales over this period allowed us to observe purchasing trends and establish a comparative January 2019 baseline for each product.

Our findings

Our analysis is presented in terms of portions, reminding us of the impact our consumer choices have in terms of our plate. To calculate this, each unit sold was translated into portions as defined by product weight, where one portion of fruit or vegetables is equivalent to 80g [2].

An impactful intervention year on year

Our first finding was pleasing, yet slightly expected: when on offer, sales increased for the promoted items.

Promoting fruit and veg increased sales by over two million portions, compared to the control year

Each year we saw an uplift in sales during the promotional period, well above the January 2019 baseline for the selected products. In total, 2.8 million more portions of promoted fruit and vegetables were sold in 2020 during the four weeks of the promotion than the previous year, across 101 stores which ran the intervention in both years. Similarly, 2.1 million more portions were sold during the 2021 promotion than in the same period in 2019, for the 101 stores.

Less impact during the national lockdown

Consumers engaged with the promotion each year, purchasing promoted products well above their 2019 levels. While both years of the promotion were successful, the second year saw slightly less impact than the first. Sales of the promoted items increased from baseline by 78% (2.8 million portions) in 2020 and by 56% (2.1 million portions) in 2021.

The 2021 trial took place during a national lockdown, when food shopping became a more pragmatic procedure. Placement and signposting were therefore probably not as strong at directing shoppers’ attention and influencing their basket.

Prior to starting our analysis, we anticipated the data may reflect effects of the pandemic alongside the effects of the trial. It is important to keep this context in mind when interpreting the data. The lower portions sold in the second year may be partly attributed to the different food landscape, however, we also have to bear in mind the differing items on promotion.

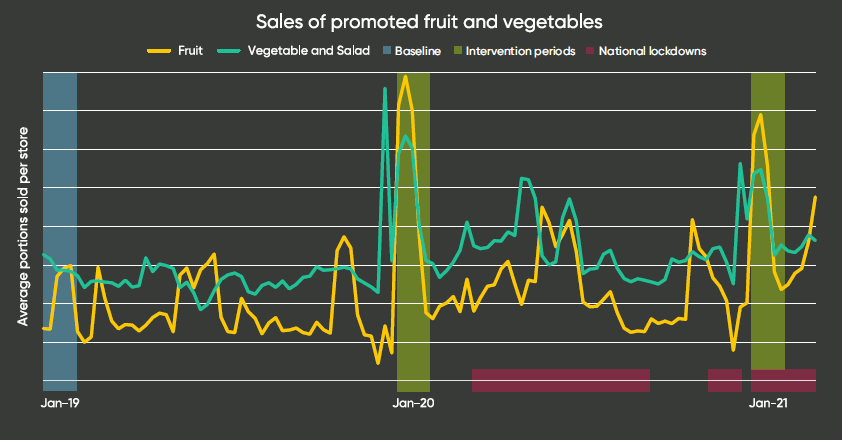

Below you can see a timeline of average portions sold per store from 2019-2021, across the 101 stores (noting it only considers items offered in the promotion). The figure illustrates seasonal shifts in consumer behaviour, essential to developing a holistic understanding of the trial’s impact.

Looking at the highlighted intervention periods, we observed a sales spike in both January 2020 and January 2021 during the promotion, emphasising those 2+million additional portions sold in each year.

Impactful, but not sustained

The timeline above plots weekly sales data. Curiously, the high level of engagement drops off in the final week of each trial. This decline may reflect people’s finances prior to payday, or may suggest that using Placement and Signposting only interrupts behaviour for a short time before going unnoticed by shoppers [3].

Some products were more appealing than others

Higher-value items were most popular, such as kale, kiwi fruit, pineapple and mango. Noticeably, these items also require minimal preparation and mostly encompassed exotic fruits. In contrast, swedes, radishes and red grapefruits were less popular in the promotion.

January – a popular month for fruits and vegetables

Important questions to understand, with the goal of encouraging people to embrace healthier and more sustainable diets, are: were customers adding items to their basket to up their fruit and vegetable content overall? Was this a shift within their usual purchasing habits?

For the last two years, around four million more units of fruit and vegetables were sold in January than the following February. Promoted items made up 9% of produce purchases during the four-week intervention period in January 2020 (dropping down to 5% in the four weeks that followed), and 8% during the four-week intervention period in January 2021 (dropping down to 6% in the four weeks that followed).

These figures indicate that the promoted items contributed to the high fruit and vegetable sales in January, but did not fully account for the uplift. There are many reasons why people may have picked up more fruit and vegetables in January, such as the growing Veganuary movement or a healthy eating New Year’s resolution. So, how do we determine the promotion’s success apart from a January health kick? Studying one year pre-intervention allowed us to establish baseline sales for the selected products. The 2+million portions sold above baseline indicates that the sales spike in January 2020 and 2021 can be largely attributed to the promotion.

Next stages

So, are promotional interventions successful? Sainsbury’s 60p Fruit and Vegetable promotion was extremely successful initially, causing a short-term sales uplift for items on offer. However, we saw this was not sustained as sales declined in the fourth week.

Our next step is then to look across people’s baskets and see what other items they were purchasing. Was their basket closer to the Eatwell Guide (the model diet we use as a metric to measure success) when engaging with the promotion?

There are many exciting developments in the wider work ahead for this partnership. More trials are underway, watch this space!

About the Author: Alexandra Dalton currently works as a Data Scientist at the Consumer Data Research Centre following her data science internship at the Leeds Institute for Data Analytics (LIDA). Alex and a team of researchers from the University of Leeds have worked in collaboration with IGD, major retailers and UK manufacturers to evaluate strategies to promote healthier and more sustainable dietary choices. She is interested by consumer data insights in the intersectional field of sustainability, nutrition and lifestyle analytics.

[1] National Food Strategy (2021). The National Food Strategy: The Plan. [Accessed online via: https://www.nationalfoodstrategy.org/ ]

[2] NHS (2018). 5 A Day: what counts? [Accessed online via: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/ ].

[3] IGD (2020) Healthy, Sustainable Diets: Driving Change [Accessed online via: https://www.igd.com/articles/ ].