Using smartphone GPS mobility data to understand population-scale responses to COVID-19 ‘lockdown’ policies in England.

Project overview

COVID-19 has prompted the enhanced use of novel mobility data in public life, offering fascinating insights into population-wide behavioural responses to Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) such as ‘lockdown’ stay-at-home orders. Here, we use privacy-preserving smartphone data to understand these trends at a regional scale over a longitudinal period spanning January 2020 to May 2021 for England, with a specific focus on examining adherence to policy measures on household visitation.

The concepts of adherence and fatigue to ‘lockdowns’ are highly debated ideas with limited observational evidence, despite their key role in supporting current policy assumptions. The SAGE report of 16th March 2020 underscored this when it said there was “(limited) evidence on whether the public will comply with the interventions in sufficient numbers and over time” (p.2) with respect to COVID-19 measures. Our study uses a novel measure of ‘house visits’ activity to cut out general noise and is explicitly purposed with better informing health policy interventions in the context of a public health emergency.

Data and methods

According to UK Government polling for the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (CDEI), 58% of over 2000 UK adults surveyed in Sept 2020 were either ‘quite comfortable’ or ‘very comfortable’ with “researchers using data to improve knowledge to help keep the public safe” during COVID-19, with just 14% being ‘quite’ or ‘very uncomfortable’. This finding was positive overall across all UK regions, all age groups, all income levels, all education levels, and whether or not people were worried about COVID-19 itself. There were also 16.5 million voluntary downloads of the NHS COVID App for modern smartphones in England and Wales in 2021. Clearly, there is a public demand for the harnessing of data to help tackle COVID-19.

Our study used anonymous, privacy-enhanced GPS smartphone mobility data from users who opted-in to data collection for research purposes under a GDPR compliant framework. Data was supplied by American and Italian location intelligence company Cuebiq, under their Data for Good program. We use unsupervised machine learning methods (DBSCAN) to make home and work area assignments, which are then taken out of user activities. Through a validated ‘process of elimination’ using POI analysis, we can then generate an aggregate measure of the proportion of de-identified users taking a house visit, for a given county area, on a given day. The output data is thus aggregated to strict privacy requirements set by Cuebiq for both temporal and spatial scales before it is analysed, yet still able to harness the precision inherent in such emerging data streams, in order to optimally inform public health policy under COVID-19. Limitations of the methods and data, including a potential lack of representativeness, were extensively discussed in the published findings. Importantly, the data could not accurately distinguish between visits to inside homes compared to outside garden areas.

Key findings

This LIDA project led to the publication of an original research paper ‘Household visitation during the COVID-19 pandemic’ in the Nature journal Scientific Reports in November 2021, detailing both methods and results.

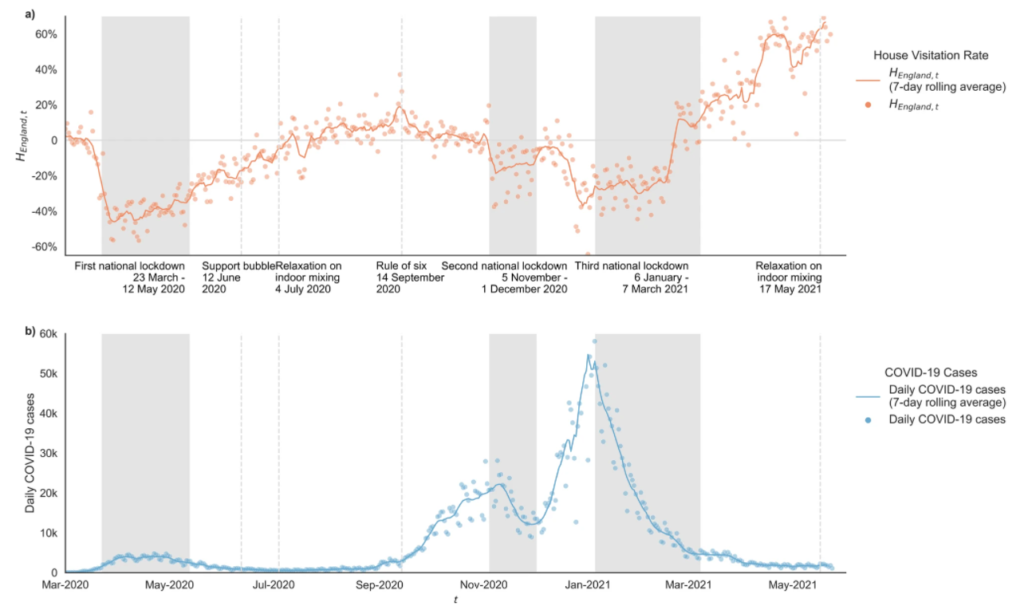

Our results track the evolution of a measure of household visitation levels in English LTLAs (Lower-Tier Local Authorities) over time – notated as ‘HEngland,t’ throughout the study. This index value was a national level, calculated through the mean average of weekly levels for each of England’s 315 LTLA areas, excluding the Isles of Scilly due to sample size issues. This weekly measure of levels of household visitation was measured against a pre-pandemic baseline figure taken from across 13th January 2020 to 2nd March 2020. The baseline was specific to both each LTLA area, as well as to each day of the week, to account for relative changes in each locality.

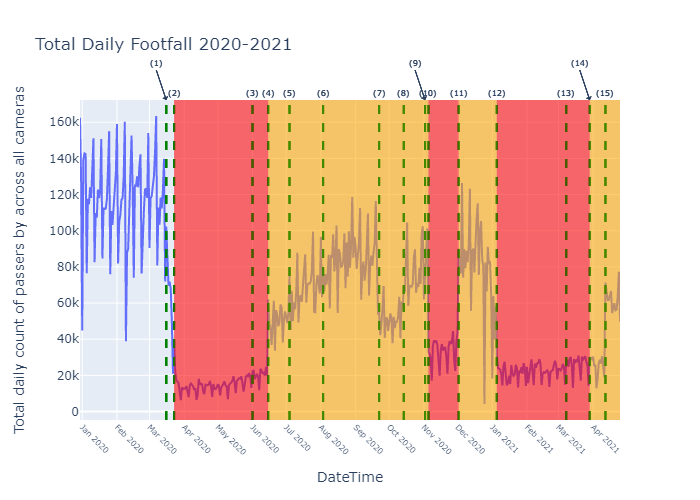

Figure 1 from the paper here shows the evolution in ‘HEngland,t’ across the full study period, as well as the evolution of recorded COVID-19 cases. As can be seen, levels of household visitation dropped dramatically in late March 2020, dropping to an all-pandemic period low of –56.4% relative to pre-pandemic baseline levels on 29th March 2020. In Figure 1 we have marked ‘national lockdown’ periods as those when stay-at-home orders were in place, during which time household visitation was prohibited in almost all cases. By taking mean averages across these time periods, we can witness household visitation levels averaging −39.33% during the 1st National Lockdown (23/03/20 – 12/05/20) below baseline levels, compared to higher rates of average house visits activity recorded during the 2nd National Lockdown (05/11/20 – 01/12/20), when rates were only averaging −15.28% below pre-pandemic levels by comparison. We didn’t witness a great jump in household visitation in the immediate aftermath of the introduction of ‘support bubble’ exemptions in mid-June 2020.

Heading into the 3rd National Lockdown (06/01/21 – 07/03/21), mobility activity reduces pointedly ahead of the imposition of national restrictions, reflecting perhaps the impact of COVID-19 risk perception and/or the new Tiered restrictions announced on 19th December 2020 in response to the detection of the new Alpha variant in South-East England. These trends were reinforced by the imposition of the 3rd National Lockdown on 6th January 2021, which kept levels of household visitation at levels between the 1st and 2nd National Lockdowns at -26.22% below (06/01/21-14/02/21) baseline rates until approximately mid-February 2021.

At this point it was announced by the Prime Minister during a 10 Downing Street Coronavirus television briefing to the nation that 15 million people from the most vulnerable categories in JCVI Priority Groups 1-4 had received a first dose of COVID-19 vaccination. Almost immediately a significant rise in household visitation rates were witnessed by our metric ‘HEngland,t’ across England, such that by the 7th March 2021 levels of household visitation were comfortably above the pre-pandemic baseline, even though coronavirus regulations had stayed the same.

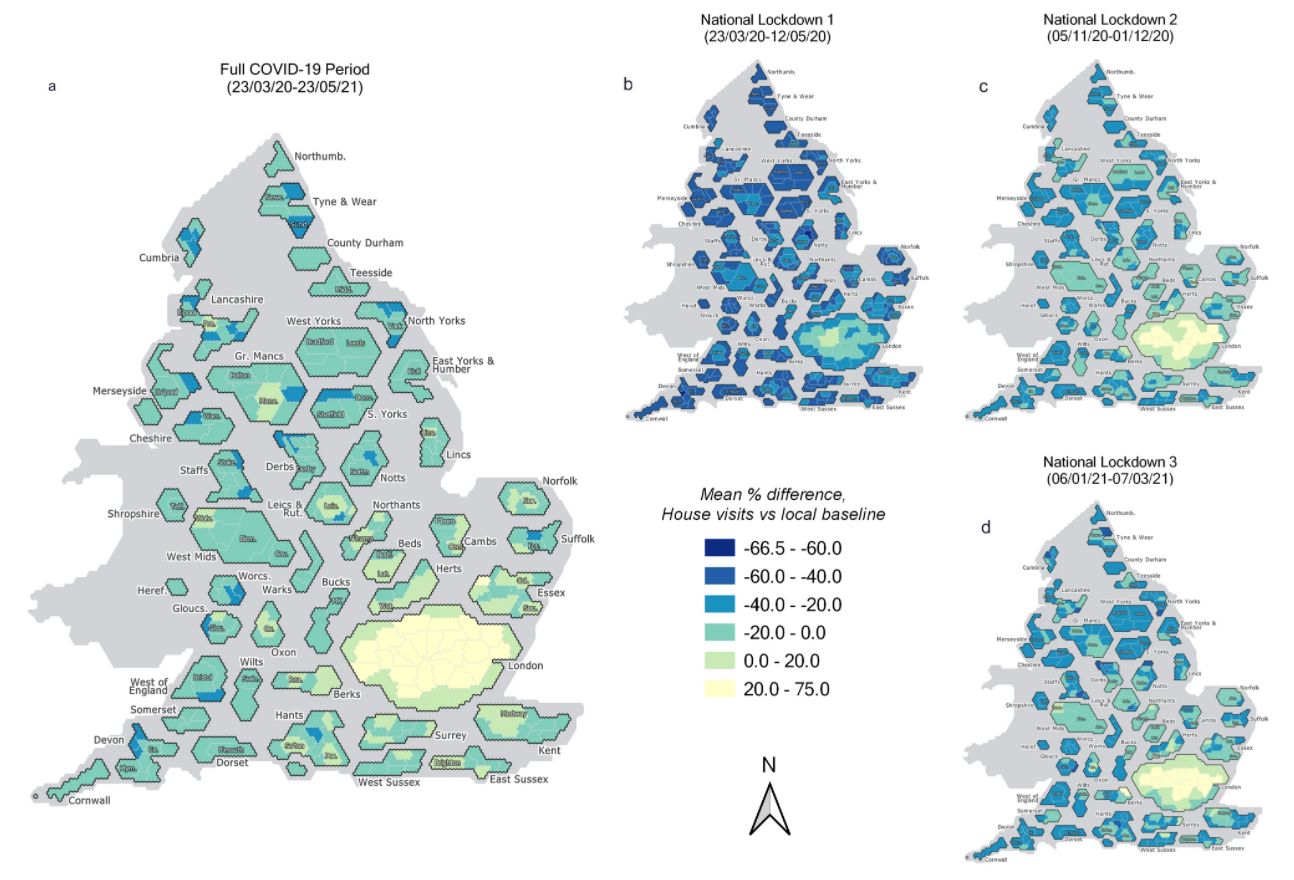

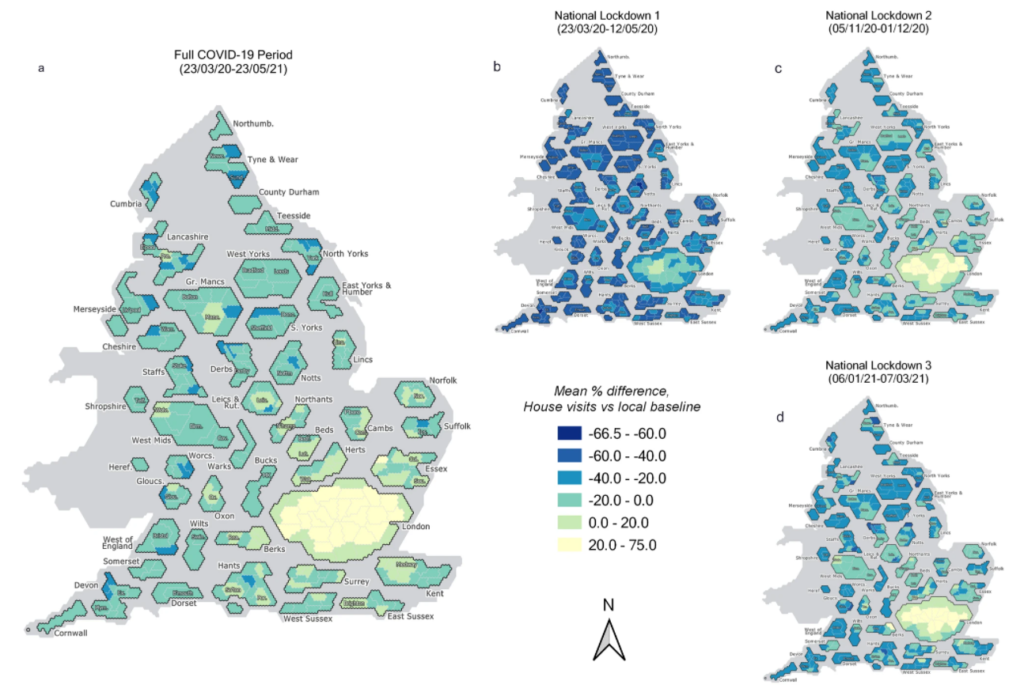

Figure 2 here illustrates the geographical variation in these household visitation rates for Local Authority Districts at LTLA scale, as mean averages across a) the entire COVID-19 period, and then, for b)-d), across the three National Lockdown periods respectively. These are presented as hex cartograms, prepared with assistance from the UK House of Commons Library. Some regional disparities are shown, notably between North and South, and between urban and rural areas. London boroughs, in particular, appear to have consistently higher relative rates of visitation against the pre-pandemic baseline than elsewhere in England.

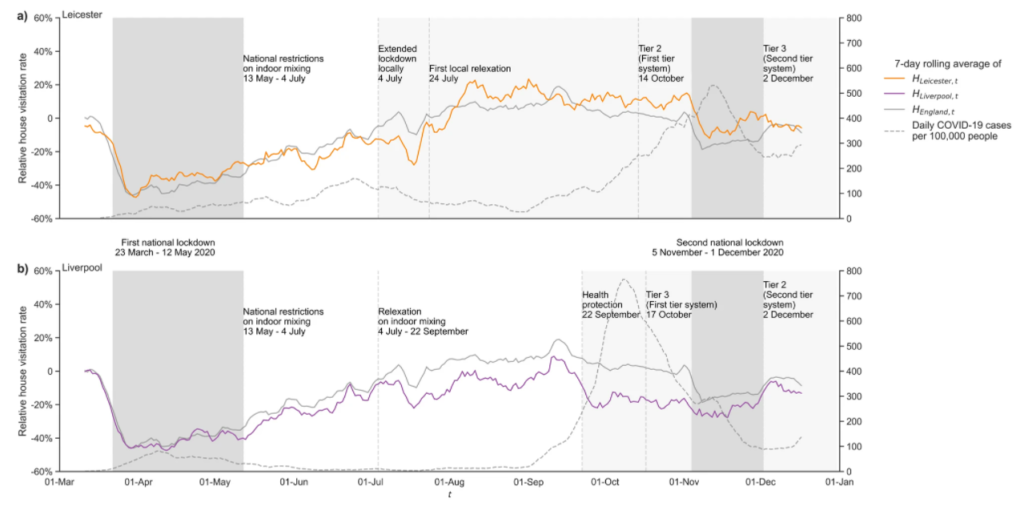

Figure 3 here finalises this summary of our key results, by showing the findings when applied to two individual local authority areas that experienced specific and rigorous local restrictions to tackle sudden outbreaks in cases over summer 2020 – ‘local lockdowns’ as they became known in England. Here, the cities of both Leicester and Liverpool are shown to have exhibited a likelihood of different profiles of adherence to ‘local lockdown’ measures on household visitation. In the case of Leicester, despite a great reduction in visitation when local lockdown was at its strictest compared to the national trajectory, a serious rise in household visits (to above the national level for England) occurs just around the time of the first relaxation on 1st August 2020, even though this didn’t revoke the restrictions prohibiting house visits. By contrast, in Liverpool house visits had stayed meaningfully below the national figure for England throughout the summer period, including after regional measures were introduced on 22nd September 2020.

Value of the research

The research had been directly designed to inform public policy, aligned with LIDA’s commitment to using data for public good. Understanding actual levels of likely aggregate adherence to pandemic policy was highlighted as an area of importance by the House of Commons Health and Technology Select Committees joint report into the UK coronavirus response – “Coronavirus: lessons learned to date” – published in September 2021.

Many activities driving virus transmission are intimately connected to the mixing and mobility of individuals. Our observational findings on behavioural responses in house visits will therefore allow public sector agencies to better understand how English populations responded to a range of lockdown impositions and relaxations, as well as allow us to see how these responses may have been complicated and/or influenced by concurrent public messaging and prevalent COVID-19 risks. A mix of past national and local lockdown policies can therefore be optimised and/or evaluated using our results. The Scientific Reports research paper disseminating the results was highlighted in the ‘Behavioural Science and Insights Unit Weekly Literature Report’ of the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) in late November 2021.

The findings received significant coverage in the national British press, featuring in Metro, The Daily Telegraph, The Independent, Daily Express, Daily Mail, The I paper, as well as in other national-scale publications including the Yorkshire Evening Post, The Conversation and current affairs magazine The Week. This was supplemented internationally by mass online coverage from Yahoo! and MSN. According to Altmetric, as of 20th January 2021, the research paper has also been shared on Twitter to a combined total of 2.69 million followers.

Quote from project partner Cuebiq

“We’re proud of the exceptional and novel research led by University of Leeds, not only because it created impactful public goods, but also because it was achieved with an uncompromising commitment to data privacy and governance.”

Insights

- Measures indicate adherence to household visitation restrictions was relatively high overall but waned both within and between subsequent National Lockdowns in England. This is rare observational evidence for shorter- and longer-term ‘fatigue’ in compliance with COVID-19 restrictions, at various stages of the pandemic lifecycle.

- About 15th February 2021, when the Prime Minister informed the nation that 15 million people from the most vulnerable in JCVI Priority Groups 1-4 had been vaccinated, a significant and unprecedented rise in household visitation rates was witnessed nationally, to above pre-pandemic base rates, despite lockdown regulations staying the same. This indicates that people may have paid meaningful attention to levels of protection carried by the most vulnerable members of British communities when determining their visiting activities, and/or have adhered far less to relevant pandemic regulations once vaccinated.

- Measures of household visitation indicate that household visitation activity was responsive to prevalent COVID-19 risk, ahead of the implementation of restrictions (i.e. Alpha variant in December 2020), as well as before they were officially lifted (1st and 3rd National Lockdowns), offering evidence individuals may respond to a perceived personal and/or collective risk of COVID-19 infection over and above current government policy or guidance.

- Local lockdowns in Leicester and Liverpool indicated a likelihood of contrasting profiles of adherence over time to ‘local lockdown’ measures prohibiting household visitation, also highlighting the potential of smartphone mobility data to indicate waning population-wide adherence in a single aggregated local authority area (where sample size N > 10 is consistently satisfied, to protect against the risks from Statistical Disclosure).

- Cuebiq mobility data for England is geographically representative across a series of temporal and spatial aggregations, and across several points in the pandemic for our sample, even if other factors of social representativeness remain rightly unknown.

Research theme

Health informatics & urban analytics.

People

Mr Stuart Ross, LIDA Data Scientist Intern

Mr George Breckenridge, LIDA Data Scientist Intern

Dr Mengdie Zhuang, Lecturer in Data Science, University of Sheffield

Prof Ed Manley, Professor of Urban Analytics & LIDA Fellow

Partners

Data provider: Cuebiq Inc., NYC, Milan

Funders: LIDA intern work funded by the CDRC (Consumer Data Research Centre), so in turn by the ESRC (Grant ES/L011891) of UKRI. Broader research project also supported by i-sense, so in turn by EPSRC (Grant EP/R00529X/1) of UKRI

Images

Open Access: Images licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, from Ross et al. (2021) Household visitation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific Reports. Springer Nature.