The grim prospect of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders is back in the news, with a number of European countries having either introduced new restrictions or reimposed full lockdowns amid rising cases. These developments inevitably raise questions around how we can best shape public health policy to reduce virus transmission.

One key challenge is reducing “risky” interactions between people, such as household visits indoors. We know close proximity and inadequate ventilation increase the chances of the virus spreading, leading to rising rates of illness. Yet our understanding of these household visitation behaviours, and the effectiveness of policy to reduce them, is lacking.

So in our latest research, we analysed mobility data collected from almost one million people in England between January 2020 and May 2021, seeking to understand trends in home visits during the pandemic.

This data was collected via location-based mobile phone apps by the data company Cuebiq, who obtained consent from users for their anonymised data to be used for research purposes. Working with Cuebiq we were able to generate aggregate analyses without obtaining any individual or household data (that is, none of the data we used could be linked to specific people).

Our interest here was in regional and national trends in mobility, and how populations moved around during the pandemic. For each region we developed indicators of visitation rates to residential areas outside of usual home areas, and assessed how these rates varied from baseline levels set in January and February 2020.

What we found

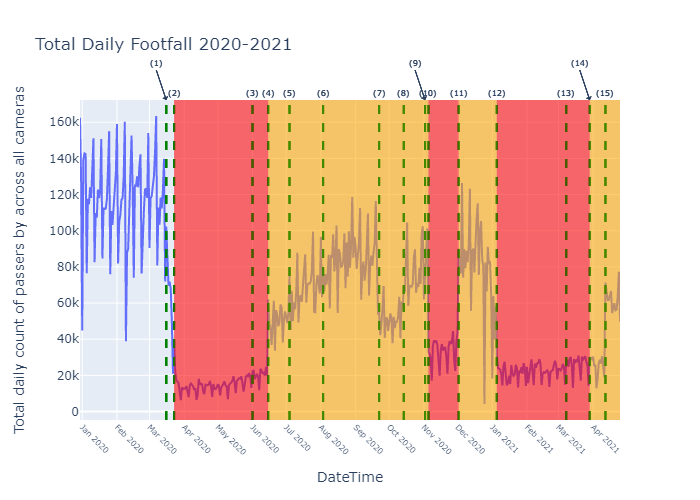

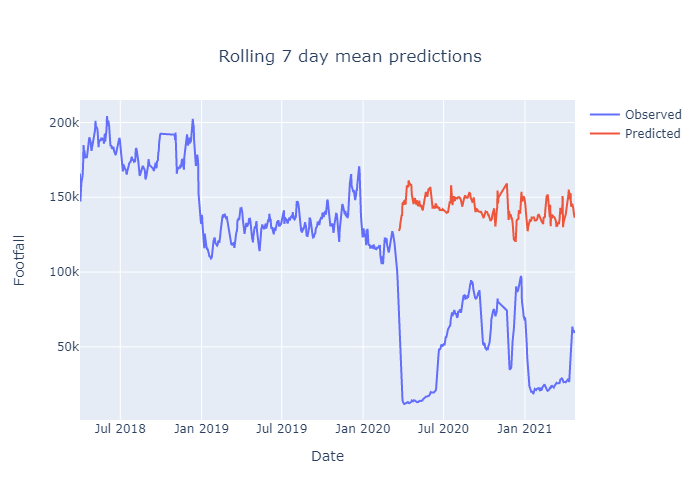

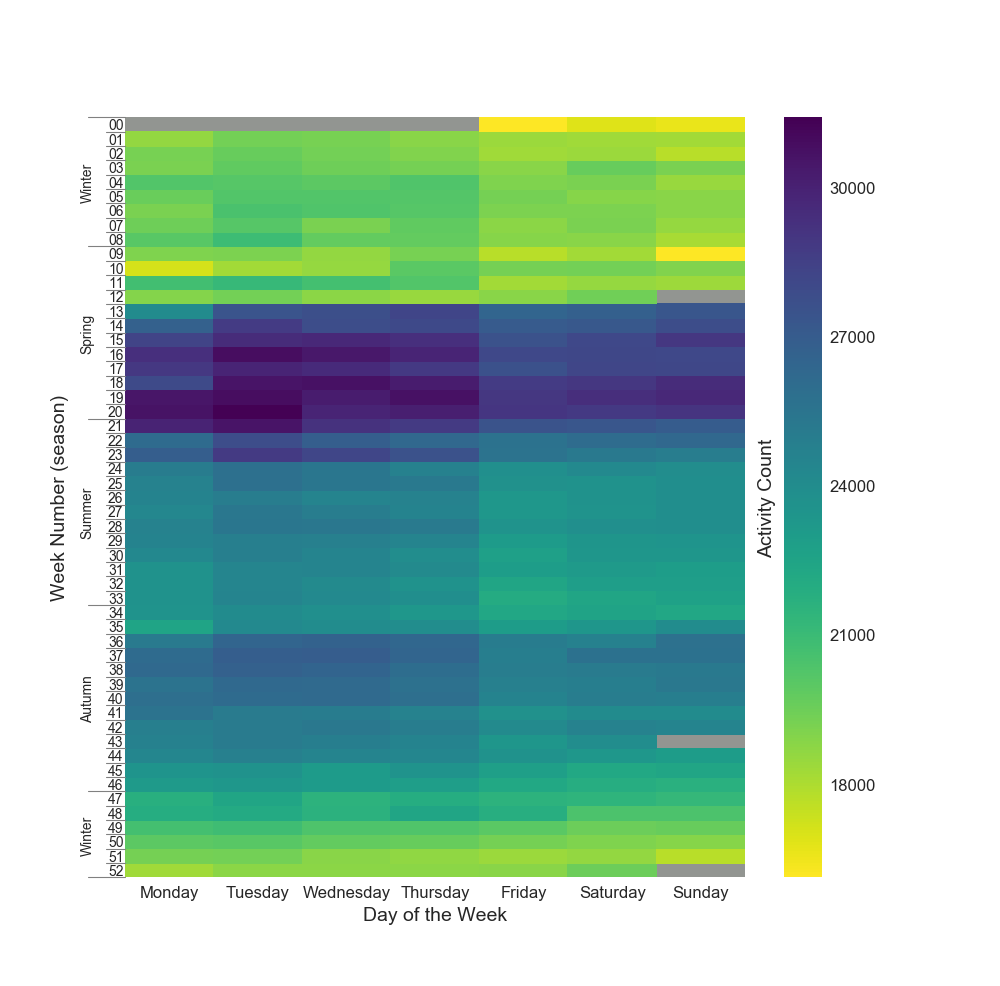

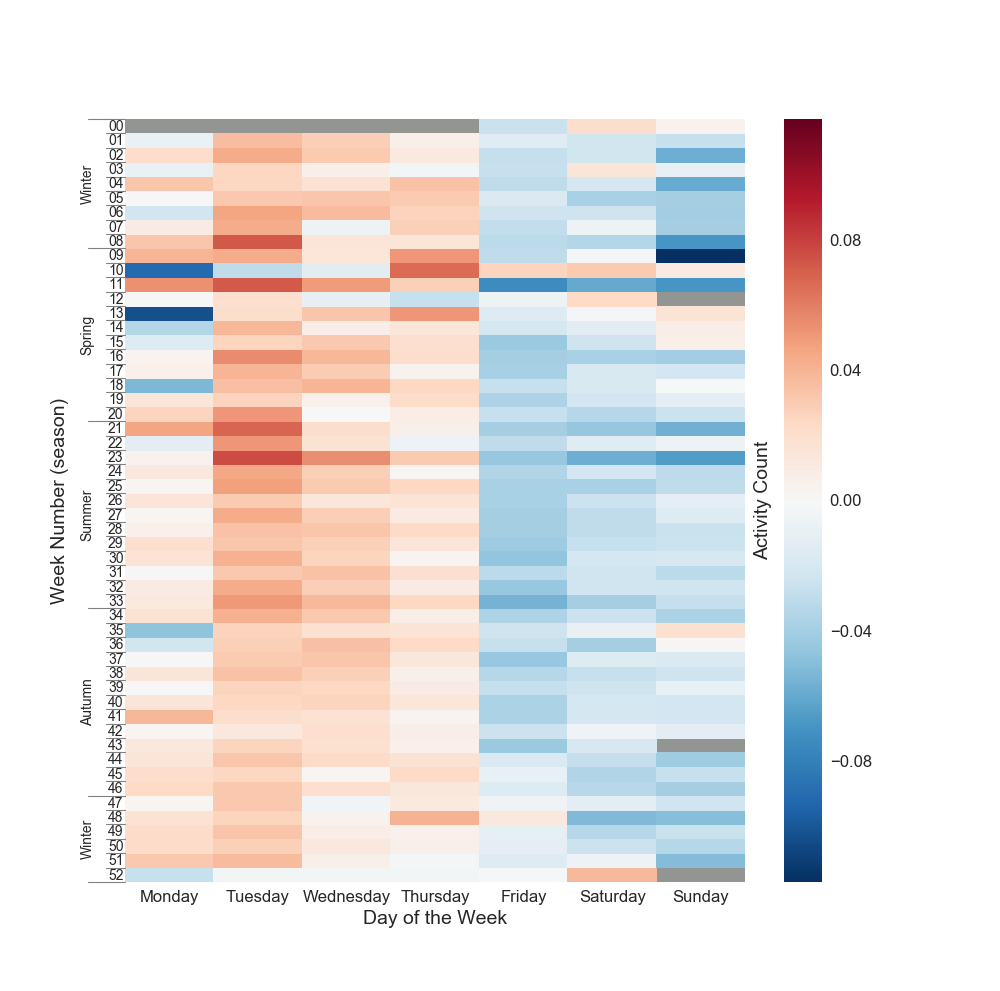

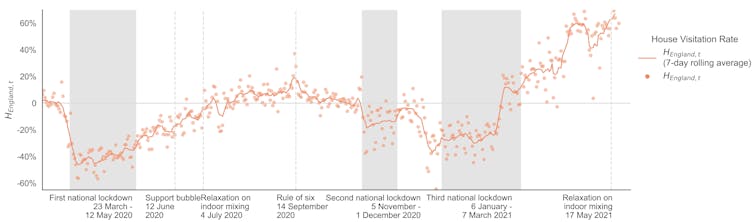

We saw a rapid reduction in people visiting other residential areas during the first lockdown in March 2020. The average decrease over the duration of the first lockdown was 39.3%, while at the lowest point, this activity was 56.4% below baseline levels. Rates of interaction increased prior to the end of the lockdown on May 12, and continued increasing through the spring and summer. But this was a gradual return.

The allowance of support bubbles in June 2020 brought no significant increase in home visits, although a flattening of the rate during August 2020 may indicate that social gatherings moved to restaurants during the operation of the Eat Out to Help Out scheme, or to public outdoor areas with warmer weather. While visitation rates exceed those seen in our baseline months, we can’t tell whether these were indoors or visits to front and back gardens, nor whether the rule of six was followed.

Later national lockdowns saw higher levels of mixing compared to what we observed in March 2020. The second lockdown in November 2020 saw a 15.3% reduction from baseline on average. Activity increased quickly after the end of the November lockdown, potentially due to the run-up to Christmas. The third lockdown, in January 2021, saw around a 26.2% reduction until mid-February.

We observed a significant rise in visitation from mid-February onwards while the third national lockdown continued – within two weeks rising to 23.3% above baseline levels. This increase in activity aligns with the announcement that the UK had offered vaccinations to the first four priority groups, which may have given people confidence to return to social activities at this time.

Taken together, the evidence suggests a slowly declining adherence to the stay-at-home rules as the pandemic went on. The underlying reasons for this will be multifaceted, summarised neatly as “lockdown fatigue”, but more precisely relate to increasing perceptions of safety in the face of the vaccine rollout, a need to re-engage in social activity, declining trust in government, and other personal stresses. These trends tell us we can’t simply pull the same policy leavers and expect to achieve the same outcomes as those seen in March 2020.

There is further variation in our findings when we look at different areas. In general, we observed lower levels of household visitation in rural areas, while some cities (London, Manchester and Cambridge, for example) regularly exceeded pre-COVID activity levels.

The reason for these differences is not clear. It could be linked to factors like household composition and personal circumstances, but further work is needed to better understand the complex demographic and household factors influencing these trends.

The implications

While there are some intriguing patterns of activity in this data, we must also apply plenty of caution in drawing conclusions. We can only speculate on the causes underlying the trends we observe, and the trends we see in England don’t necessarily reflect what has happened, or might happen, elsewhere.

Nevertheless, these findings add to our understanding of the impacts of pandemic policy, and highlight the need for nuance in crafting future interventions.

The patterns of household visitation we observed reflect the social complexities of the pandemic period. We must remember that household visitation does not equate to malicious noncompliance, and instead may point to the need for people to see each other for their emotional wellbeing.

While there are clear public health reasons to encourage caution in social mixing, this must be balanced against the negative outcomes of lockdowns and their potentially diminishing returns. Policy must be crafted to account for these nuances – supporting opportunities to socialise while avoiding higher risk interactions, responding locally, and adapting with the changing attitudes and circumstances faced by the population.

Ed Manley, Professor of Urban Analytics, University of Leeds and Mengdie Zhuang, Lecturer in Data Science, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.